WIAD 2019 - Mapmaking in Physical and Digital Space

Sarah Barrett and Rachel Price, two Senior Information Architects from Microsoft, held a workshop on Mapmaking in Physical and Digital Space at WIAD (World Information Architecture Day) this year in Zurich. The content was well-researched, easy to process, and relevant to both UX students and practitioners. In this post, I focus on the basics of maps and mapping in the digital world and also cover the eight wayfinding principles.

Note: Sarah and Rachel provided a useful summary of topics for attendees, and my content is pulled from this.

Maps and Mapping

Most people find it easier to navigate the real world than the digital world. It’s usually easier, for example, to tell a housesitter over the phone where the bathroom is in your apartment than to explain to them how to find a document on your computer.

“Intuitively, people can feel their brains being good at understanding things like rooms and tables, and they can feel them being bad at understanding software, apps, and websites.” - Sarah and Rachel

Digital experiences should be designed according to the same principles that people’s brains expect from physical experiences. One of the main tools for understanding is the process of mapping. According to Sarah and Rachel, the average person is “very good at making sense of and remembering certain kinds of spaces.”

Landscapes vs. Tabletops

Everyone creates maps, but we don’t handle all spaces the same way. Research suggests that we understand spaces as either tabletops or landscapes:

Wayfinding Principles

Part of the workshop focused on eight wayfinding principles applied to landscapes. Since attending the workshop, I often use these principles to explain design concepts to people outside the discipline and to reinforce my own design decisions.

As designers, it’s important that we help people make sense of digital landscapes by making them as legible as possible. The best way to do this is to include UI and/or content elements that follow Mark Foltz’s Design Principles for Wayfinding. I’ve thought up some real world analogies from locations in Bern, home of Puzzle ITC’s main office to clarify the principles.

1. Identify Locations

Tell the user where they are, and give it a name so they can refer back to it. Examples:

- Real World - Like Puzzle ITC in Bern, buildings have numbers and companies have names which helps people find them.

- Digital World - Placing a logo top left consistently helps users identify their location as on the Puzzle ITC website.

2. Create Edges

Large spaces should be divided into regions with edges creating perceivable differences between them. This helps people understand where they are within a larger space. Examples:

- Real World - In a city, cafés often look a certain way that’s different from the surrounding area so people can immediately tell where they are. In the photo, a café in Bern uses plants as a divider between the restaurant and its surroundings.

- Digital World - Designers create edges by making two sections look different. The Hitobito header is separated from site content with color and font variation.

3. Pave Your Paths

While people can move in many different directions, it’s easiest for them to find their way if the landscape clearly indicates recommended paths. These paths should be continuous, show which direction a person is traveling as they move, and indicate the distance back to the beginning or to the end at a quick glance. Examples:

-

Real World - The Bearpark along the river Aare has paths that provide easy routes without requiring people (or bears) to make their way through shrubs and mud.

-

Digital World - As in this example from a current SwissPass project, designers make sure check-out paths are very clear, often with indications of what each step entails and how far through the process the customer is at any moment.

4. Add Landmarks

Landmarks are elements that a person won’t necessarily interact with, but they provide an orientation cue and make locations more memorable. Landmarks are usually visible from many locations and change in some predictable way relative to a person’s movement through space. Examples:

-

Real World - Rising above Bern, the Münster is visible from many areas, and it helps people tell their orientation in the city relative to it.

-

Digital World - On the APPUiO website, the navigation bar never changes position acting as a landmark for users.

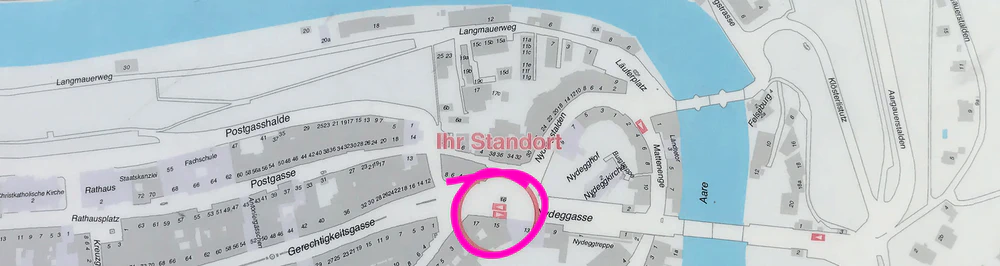

5. Make maps

Maps help people to understand their position relative to the whole.

-

Real World - Maps around Bern show people where they are currently located relative to the entire city. Many times, as in the case of subway systems, these maps are more useful when they are symbolic, rather than literal.

-

Digital World - a megamenu showing users an overview of the entire Etsy website and where they currently are located.

6. Establish Sight lines

It is always more effective to let people see where they can go rather than telling them. A long but narrow view into what might be ahead lets people make informed decisions about where they might go. Examples:

-

Real World - The main station in Bern is built off one large, open space. This ensures that people can see a long way and can use those sightlines to identify signage to find platforms, the ticket counter, bus lines, etc.

-

Digital World - In the BLS app, designers provide subtitles below links to help people anticipate what is behind the click and determine which direction they want to go.

7. Add Signs

People need signs at points where they must make a decision. Signs should be scaled so people aren’t overwhelmed with specific information before it’s useful to them.

- Real World - Signs showing hikers how long to different destinations when they arrive at an intersection.

- Digital World - Metadata often functions as useful signage for users. On the Appuio website, the “most chosen” product option is tagged to orient people to popular choices.

8. Limit Choices

Users do not need all choices at once; scaffold information for users as appropriate. Most landscapes offer a huge variety of potential options but are constructed that only a few make sense at any given point. It is much easier to make a series of choices in which each choice opens up others logically related to it rather than being presented with the totality all at once. Examples:

-

Real World - Grocery stores group items based on their characteristics so a customer looks in a given area depending on what kind of item they want. Within these groups, similar kinds of items are often grouped together.

-

Digital World - The SBB train connection search instructs users first to select arrival and departure stations. Users then progressively select other options like time, price, and seat options rather than choosing everything at once.